Passengers of the Far Eastern train, passing through Transbaikalia, involuntarily pay attention to the name of the station "Erofey Pavlovich". Not everyone knows whose name the Russian people named this station. But a knowledgeable person will proudly explain that the station is named after the brave Russian explorer Yerofei Pavlovich Khabarov. A large city in the Far East, Khabarovsk, is named after him.

Erofey Khabarov is one of those remarkable Russian people who over three hundred years ago in a short time passed from the Ural Mountains to the shores of the Pacific Ocean, joining the Siberian lands to the Russian state.

Information about the time of birth, childhood and youth of Khabarov has not been preserved. It is only known that he was from Ustyug and at the beginning of the 17th century. was engaged in cooking salt in the city of Solvychegodsk. But things probably didn't go well; Khabarov went to seek his fortune in the new Siberian lands.

Settling first on the Yenisei, he soon moved to the Lena, where he was engaged in sable fishing.

Having found the salt springs, Khabarov again began to boil the salt. She was needed by everyone, and things went well.

For the first time in this region, Khabarov also took up farming. But soon the Yakut governor took away from him the salt pan, all the arable land and 3,000 pounds of bread for the treasury, and Khabarov himself, for some unknown reason, was put in the Yakut prison.

Having left prison ruined, Khabarov became interested in stories about the Amur land, about its unheard-of riches. He decided to try his luck in this new, recently discovered country, where none of the Russians had gone before Poyarkov and his companions.

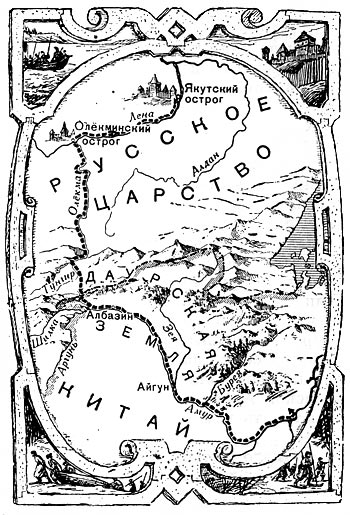

In 1649, the voivode was changed in Yakutsk, and Khabarov suggested that the new voivode Frantsbekov send him with a detachment of Cossacks to the Amur to "find new lands." The governor willingly agreed to Khabarov’s proposal and instructed him to select a detachment from those who wanted to go to the Amur lands, which at that time were inhabited by the tribes of Tungus, Daurs, Duchers, Achans, Gilyaks, etc. They lived disunitedly and experienced many troubles from Manchu merchants, who mercilessly they were deceived.

There were few hunters to share the difficulties of camp life with Khabarov: the Cossacks were frightened by the stories of Poyarkov's companions about the dangers they encountered. Khabarov barely managed to recruit about 80 people into the detachment.

The voivode instructed him not only to collect yasak from local residents, but also to describe their life and draw up "drawings" (maps) of the area with descriptions of natural conditions.

In the summer of 1649 Khabarov set out from Yakutsk. At that time in Siberia the only accessible roads were the rivers. Khabarov decided to get to the Amur, first along the rivers of the Lena basin, and then, in the place where the upper reaches of its tributaries converge most closely with the upper reaches of the Amur tributaries, to cross to the Amur basin by drag.

From Yakutsk he sailed up the Lena to the mouth of its large tributary, the Olekma. The boats moved slowly up the fast and rapid Olekma. Sometimes on the thresholds people were completely exhausted. Khabarov wrote: “In the rapids, tackle was torn, bastards were broken, people were bruised ...”

Only in the late autumn of 1649 did the detachment reach the mouth of the right tributary of the Olekma - the Tugir, where they had to spend the winter.

In January, having made sledges and loaded boats and all property on them, the Cossacks moved through the high Stanovoy Range. It was hard to pull the loaded sledges uphill. In addition, strong winds and blizzards made progress difficult. Finally, having crossed the ridge, Khabarov reached the river. Urku and went down to the Amur along it. Already in the upper reaches of the Amur, the Cossacks met the villages of local residents - Daurs. These were well-fortified cities, surrounded by high wooden walls with towers and deep moats. But they were abandoned by the inhabitants, frightened by the approach of the Cossacks.

In one of these cities, the detachment stopped to rest. Once sentries reported to Khabarov that horsemen were approaching the city. It was the local Daurian prince Lavkai. He asked through an interpreter what kind of people occupied their city. Khabarov replied that they had come to Dauria to trade. At the same time, he offered the prince to pay yasak, promising the patronage of the Russian Tsar for this. Lavkay gave an evasive answer and left.

Not daring to go deep into the country with insignificant forces, Khabarov left most of his detachment in the village, and he himself went to Yakutsk for reinforcements. With delight, he told the governor about the riches of the Daurian land, about the fertility of its fields, about the forests, fur-bearing animals and the fish wealth of the Amur. If the Daurs are forced to pay yasak, he said, then Yakutsk will be fully provided with bread from the banks of the Amur, since this land "against all Siberia will be decorated and abundant with everything."

This time around 180 people were recruited for the campaign. In July 1650, Khabarov set out with his detachment from Yakutsk and reached the Amur in the autumn.

In his absence, the Daurs repeatedly attacked the abandoned detachment, which had to endure more than one siege. But the Russians, significantly inferior to the Daurs in numbers, nevertheless emerged victorious: the Daurs were armed with bows and arrows, and the Cossacks were armed with guns.

The news of the brave Cossack Khabarov reached Moscow. In order to secure new lands for Russia, a detachment of 132 service and industrial people with a supply of gunpowder and lead was additionally sent to Khabarov at the disposal of Khabarov.

In the summer of 1651, Khabarov sailed down the Amur, conquering the Daurian cities and taxing the population with sable yasak.

Behind Dauria began the country of Achans engaged in fishing. At one of the Achan uluses (villages) Khabarov found winter. The Achans were stronger than the Daurs and offered resistance to Khabarov. Tracking down the Russians and ferreting out their forces, they continually tried to attack them.

Stopping for the winter, Khabarov sent some of the people down the Amur. Seeing that Khabarov's detachment had decreased, the Achans boldly attacked the Russians. But, despite a significant numerical superiority, the Achans could not resist the Cossacks and fled from the battlefield in a panic. Khabarov overlaid them with yasak. They paid it regularly, but at the same time they secretly turned to the Manchu princes for help. In the spring of 1652, the Manchus sent a large army, well armed with firearms, to the town of Achan. A fierce battle ensued, which ended in the complete defeat of the Manchus.

While Khabarov fought with the Achans and Manchus, he did not give any news about himself. The Yakut governor, worried about such a long silence, decided to send reinforcements. A detachment sent from Yakutsk met Khabarov on the way. Although Khabarov received 144 men, guns and even a cannon as reinforcements, there was no question of resuming the campaign down the Amur. It became known from local residents that the Manchu feudal lords, alarmed by the penetration of the Russians into the Amur, decided to send a large and well-armed army against the Cossacks. Khabarov reasoned that it was risky for him to engage in battle with the main forces of the Manchus.

The detachment of Khabarov stopped near the mouth of the river. Zeya, where the Cossacks were going to build a city. Part of the detachment refused to obey Khabarov. One hundred and thirty-six Cossacks, led by Kostya Ivanov, sailed down the Amur.

Khabarov had only about two hundred people left. He sent four Cossacks to Yakutsk with a report to the governor, asking him for advice and help. It was clear to Khabarov that without significant reinforcements he would not be able to keep such a vast region in subjection.

At the same time, Khabarov decided to overtake the rebels and punish them. On September 30, 1652, he appeared under the walls of their town and built his winter hut nearby. After careful preparation, Khabarov opened hostilities. The whole day the detachment shelled the town. Finally, the besieged surrendered. They were severely punished; many were beaten to death with batogs.

Khabarov spent the winter in the captured town, and in the spring, having destroyed it, again sailed up the Amur.

Reports about Khabarov's campaign went to Yakutsk and Moscow. The government decided to send a governor and 3,000 archers to the Amur. First, Zinoviev, an official of the Siberian Order, was sent to the Amur with a detachment of 150 people in order to organize a new Daurian Voivodeship and prepare for the acceptance of a large army on the spot.

While Zinoviev was getting to Dauria, a rumor quickly spread throughout Siberia about the riches of the new land. From all over the vast Siberian land, Russian people reached for the Amur. The Yakut governor, worried about the mass departure of people from the banks of the Lena, sent a chase after them, but those sent often joined the settlers. In order to keep people out of the Amur, the governor had to arrange a special outpost on Olekma.

Zinoviev met with Khabarov at the mouth of the Zeya in August 1653. After distributing royal awards, Zinoviev told Khabarov that he was instructed to "inspect the entire Daurian land." In other words, Khabarov retired from business and Zinoviev became the head. Part of the Cossacks, dissatisfied with Khabarov, took advantage of this. They began to accuse Khabarov of all kinds of harassment, and most importantly, that he “did not care for the state cause, but cared for his belongings, sable fur coats ...” Zinoviev took Khabarov’s property for himself, arrested him and took him to Moscow, accusing him of a state crime.

In Moscow, in the Siberian order, the investigation of the case began. In a petition submitted to the tsar, Khabarov asked for his service, for the fact that he “shed his blood and endured his wounds” and “brought 4 lands under the sovereign’s hand”, to return the property taken by Zinoviev. Khabarov's request was granted. In addition, for services to the Russian state, he received an award and was appointed manager of the settlements along the Lena. Zinoviev was punished for abuse of power and misappropriation of Khabarov's property.

Later, Khabarov more than once filed petitions to the governors with a request to send him back to the Daurian lands "for urban and prison deliveries and for settlements and plowing." But every time he was refused.

How the fate of Khabarov developed in the future is not exactly known.

Erofei Khabarov, adding new lands to Russia, first of all, strove for the economic use of the Amur region. In one of the reports to the Yakut governor, he wrote about the riches of the region: “And a lot of Tunguses live along those rivers, and down the glorious Amur River live Daurian arable and cattle people, and in that great Amur River there are fish - kalushka, and sturgeons, and there are many fish against the Volga. And in the cities and uluses there are great meadows and arable lands, and the forests along that great Amur River are dark, large, there are many sables and all kinds of animals ... And gold and silver can be seen in the earth. There is even information that Khabarov tried to engage in agriculture on the Amur, organizing settlements from Russian settlers for this.

If you find an error, please highlight a piece of text and click Ctrl+Enter.