The history of Russia is connected with many Russian sea expeditions of the 18th–20th centuries. But a special place among them is occupied by round-the-world voyages of sailing ships. Russian sailors later than other European maritime powers began to make such voyages. By the time the first Russian circumnavigation of the world was organized, four European countries had already made 15 such voyages, starting with F. Magellan (1519–1522) and ending with the third voyage of J. Cook. Most of the round-the-world voyages on account of English sailors - eight, including three - under the command of Cook. Five voyages were made by the Dutch, one each by the Spaniards and the French. Russia became the fifth country in this list, but in terms of the number of round-the-world voyages, it surpassed all European countries combined. In the 19th century Russian sailing ships made more than 30 full circumnavigations and about 15 semi-circumnavigations, when the ships that arrived from the Baltic to the Pacific Ocean remained to serve in the Far East and Russian America.

Failed expeditions

Golovin and Sanders (1733)

For the first time in Russia, Peter I thought about the possibility and necessity of long-distance voyages. He intended to organize an expedition to Madagascar and India, but did not manage to carry out his plan. The idea of a round-the-world voyage with a call to Kamchatka was first expressed by the flagships of the Russian fleet, members of the Admiralty Board, Admirals N. F. Golovin and T. Sanders in connection with the organization of the Second Kamchatka Expedition. In October 1732, they submitted to the Senate their opinion on the expediency of sending an expedition "from St. Petersburg on two frigates through the Great Sea-Okiyan around the Gorn cap and into the Western Sea, and between the Japanese islands even to Kamchatka."

They proposed to repeat such expeditions annually, replacing some ships with others. This was supposed to allow, in their opinion, in a shorter time and better organize the supply of V. Bering's expedition with everything necessary, and quickly establish trade relations with Japan. In addition, a long voyage could become a good sea practice for officers and sailors of the Russian fleet. Golovin suggested that Bering himself be sent to Kamchatka by land, and he asked to entrust the navigation of two frigates to him. However, the ideas of Golovin and Sanders were not supported by the Senate and the opportunity to organize the first Russian voyage in 1733 was missed.

Krenitsyn (1764)

In 1764, it was decided to send around the world to Kamchatka an expedition of Lieutenant Commander P. K. Krenitsyn, but because of the impending war with Turkey, it was not possible to carry it out. The voyage, which I. G. Chernyshev, vice-president of the Admiralty Board, tried to equip in 1781, also did not take place. In 1786, the head of the "North-Eastern ... Expedition", Lieutenant Commander I. I. Billings (participant in Cook's third voyage), presented to the Admiralty Board the opinion of his officers that, at the end of the expedition, the return route of her ships would lie around Cape Good Hopes in Kronstadt. He was also denied.

But on December 22 of the same 1786, Catherine II signed a decree of the Admiralty Board on sending a squadron to Kamchatka to protect Russian possessions: ours to the lands discovered by Russian navigators, we order our Admiralty Board to send from the Baltic Sea two ships armed according to the example used by Captain English Cook and other navigators for similar discoveries, and two armed boats, sea or other ships, at her best discretion, appointing them go around the Cape of Good Hope, and from there, continuing the path through the Sonda Strait and, leaving Japan on the left side, go to Kamchatka.

The Admiralty Board was instructed to immediately prepare the proper instructions for the expedition, appoint a commander and servants, preferably from volunteers, make orders for arming, supplying and dispatching ships. Such a rush was associated with a report to Catherine by her secretary of state, Major General F. I. Soymonov, about the violation of the inviolability of Russian waters by foreigners. The reason for the report was the entry into the Peter and Paul Harbor in the summer of 1786 of a ship of the English East India Company under the command of Captain William Peters in order to establish trade relations. This was not the first time that foreigners appeared in Russian possessions in the Pacific Ocean, which caused the authorities to worry about their fate.

As early as March 26, 1773, Prosecutor General Vyazemsky, in a letter to the Kamchatka commandant, admitted the possibility of a French squadron appearing off the coast of Kamchatka in connection with the case of M. Benevsky. In St. Petersburg, news was received that a flotilla and 1,500 soldiers were being equipped in France for Benevsky. It was about equipping Benevsky's colonial expedition to Madagascar, in which twelve Kamchatka residents who fled with Benevsky also took part. But in Petersburg they suspected that, since Benevsky knew well the disastrous state of the defense of Kamchatka and the way there, this expedition could go to the peninsula.

In 1779, the governor of Irkutsk reported the appearance of unrecognized foreign ships in the area of the Chukotka nose. These were Cook's ships, heading from Petropavlovsk in search of a northwestern passage around America. The governor proposed to bring Kamchatka into a "defensive position", since the way to it became known to foreigners. The entry of Cook's ships into the Peter and Paul harbor in 1779 could not but alarm the Russian government, especially after it became known that the British put on their maps the American coasts and islands long discovered by Russian navigators and gave them their names. In addition, in St. Petersburg it became known that in 1786 the French expedition of J. F. La Perouse was sent on a round-the-world voyage. But it was still unknown about the expedition in the same year of Tokunai Mogami to the southern Kuril Islands, which, after collecting yasak Iv. Cherny in 1768 and the Lebedev-Lastochnik expedition in 1778-1779, Russia considered its own.

All this forced Catherine II to order the President of the College of Commerce, Count A. R. Vorontsov, and a member of the College of Foreign Affairs, Count A. A. Bezborodko, to submit their proposals on the issue of protecting Russian possessions in the Pacific Ocean. It was they who proposed sending a Russian squadron on a round-the-world voyage and declaring to the sea powers about the rights of Russia to the islands and lands discovered by Russian sailors in the Pacific Ocean.

Mulovsky (1787)

The proposals of Vorontsov and Bezborodko formed the basis of the above-mentioned decree of Catherine II of December 22, 1786, as well as the instructions of the Admiralty Board to the head of the first round-the-world expedition of April 17, 1787.

After discussing various candidates, 29-year-old Captain 1st Rank Grigory Ivanovich Mulovsky, a relative of the vice-president of the Admiralty College I. G. Chernyshev, was appointed head of the expedition. After graduating from the Naval Cadet Corps in 1774, he served for twelve years on various ships in the Mediterranean, Black and Baltic Seas, commanded the frigates Nikolai and Maria in the Baltic, and then a court boat that sailed between Peterhof and Krasnaya Gorka. He knew French, German, English and Italian. After a campaign with Sukhotin's squadron in Livorno, Mulovsky received the command of the David of Sasunsky ship in the Chichagov squadron in the Mediterranean Sea, and at the end of the campaign he was appointed commander of the John the Theologian in Cruz's squadron in the Baltic.

The list of tasks of the expedition included various goals: military (fixing Russia and protecting its possessions in the Pacific Ocean, delivery of fortress guns for the Peter and Paul Harbor and other ports, foundation of a Russian fortress in the southern Kuriles, etc.), economic (delivery of necessary goods to Russian possessions, livestock for breeding, seeds of various vegetable crops, trading with Japan and other neighboring countries), political (assertion of Russian rights to lands discovered by Russian sailors in the Pacific Ocean, by installing cast-iron coats of arms and medals depicting the Empress, etc.) , scientific (drawing up the most accurate maps, conducting various scientific studies, studying Sakhalin, the mouth of the Amur and other objects).

If this expedition were destined to take place, then now there would not be a question about the ownership of the southern Kuriles, seventy years earlier Russia could have begun the development of the Amur region, Primorye and Sakhalin, otherwise the fate of Russian America could have been formed. There were no round-the-world voyages on such a scale either before or since. At Magellan, five ships and 265 people participated in the expedition, of which only one ship with 18 sailors returned. Cook's third voyage had two ships and 182 crew members.

The squadron of G. I. Mulovsky included five ships: Kholmogor (Kolmagor) with a displacement of 600 tons, Solovki - 530 tons, Sokol and Turukhan (Turukhtan) - 450 tons each, and transport ship "Courageous". Cook's ships were much smaller: Resolution - 446 tons and 112 crew members and Discovery - 350 tons and 70 people. The crew of the flagship Kholmogor under the command of Mulovsky himself consisted of 169 people, Solovkov under the command of Captain 2nd Rank Alexei Mikhailovich Kireevsky - 154 people, Sokol and Turukhan under the command of lieutenant commanders Efim (Joachim) Karlovich von Sievers and Dmitry Sergeevich Trubetskoy - 111 people each.

The Admiralty Board promised the officers (there were about forty) extraordinary promotion to the next rank and a double salary for the duration of the voyage. Catherine II personally determined the procedure for rewarding Captain Mulovsky: “when he passes the Canary Islands, let him declare himself the rank of brigadier; having reached the Cape of Good Hope, to entrust him with the Order of St. Vladimir 3rd class; when it reaches Japan, he will already receive the rank of major general.

An infirmary for forty beds with a learned doctor was equipped on the flagship ship, and assistant doctors were assigned to other ships. A priest was also appointed with a clergy to the flagship and hieromonks to other ships.

The scientific part of the expedition was entrusted to Academician Peter Simon Pallas, promoted on December 31, 1786 to the rank of historiographer of the Russian fleet with a salary of 750 rubles. in year. For "maintaining a detailed travel journal in a clean calm" secretary Stepanov, who studied at Moscow and English universities, was invited. The scientific detachment of the expedition also included astronomer William Bailey, a member of Cook's voyage, naturalist Georg Forster, botanist Sommering and four painters. In England, it was planned to purchase astronomical and physical instruments: Godley's sextants, Arnold's chronometers, quadrants, telescopes, thermo- and barometers, for which Pallas entered into correspondence with the Greenwich astronomer Meskelin.

The library of the flagship included over fifty titles, among which were: “Description of the Land of Kamchatka” by S. P. Krasheninnikov, “General History of Travels” by Prevost Laharpe in twenty-three parts, the works of Engel and Dugald, extracts and copies of all magazines of Russian voyages in the Eastern Ocean from 1724 to 1779, atlases and maps, including the "General Map, which presents convenient ways to increase Russian trade and navigation in the Pacific and Southern Oceans", composed by Soymonov.

The expedition was prepared very carefully. A month after the decree, on April 17, the crews of the ships were assembled, all the officers moved to Kronstadt. The ships were raised on the stocks, work on them was in full swing until dark. Food was delivered to the ships: cabbage, 200 pounds for each salted sorrel, 20 pounds for dried horseradish, 25 pounds for onions and garlic. From Arkhangelsk, 600 pounds of cloudberries were delivered by special order, 30 barrels of sugar syrup, more than 1000 buckets of sbitnya, 888 buckets of double beer, etc. It was decided to buy meat, butter, vinegar, cheese in England. In addition to double uniform ammunition, the lower ranks and servants relied on twelve shirts and ten pairs of stockings (eight wool and two thread).

“To approve the Russian right to everything hitherto committed by Russian navigators, or newly made discoveries”, 200 cast-iron coats of arms were made, which were ordered to be strengthened on large pillars or “along the cliffs, hollowing out a nest”, 1700 gold, silver and cast-iron medals with inscriptions in Russian and Latin, which should have been buried in "decent places".

The expedition was well armed: 90 cannons, 197 jaegers, 61 hunting rifles, 24 fittings, 61 blunderbuss, 61 pistols and 40 officers' swords. It was allowed to use weapons only to protect Russian rights, but not to the natives of the newly acquired lands: “... there should be the first effort to sow in them a good idea about the Russians ... It is highly forbidden for you to use not only violence, but even for any parties to brutal acts of vengeance".

But with regard to foreign aliens, it was instructed to force them “by right, before the discoveries made to the Russian state, belonging to the places, to leave as soon as possible and henceforth neither about settlements, nor about trading, nor about navigation; and if there are any fortifications or settlements, then you have the right to destroy, and to tear down and destroy signs and emblems. You should do the same with the ships of these aliens, in those waters, harbors or on the islands you will meet those who are able for similar attempts, forcing them to leave from there for the same reason. In the case of resistance, or, rather, strengthening, by using the force of arms, since your ships are so well armed to this end.

On October 4, 1787, the ships of the Mulovsky expedition, in full readiness for sailing, stretched out on the Kronstadt roadstead. The Russian minister-ambassador in England had already ordered pilots, who were waiting for the squadron in Copenhagen to escort it to Portsmouth.

But an urgent dispatch from Constantinople about the beginning of the war with Turkey crossed out all plans and works. The highest command followed: “The expedition being prepared for a long journey under the command of Captain Mulovsky’s fleet, under the present circumstances, should be postponed, and both officers, sailors and other people assigned to this squadron, as well as ships and various supplies prepared for it, should be turned into the number of that part fleet of ours, which, according to our decree of the 20th of this month, the Admiralty Board given, should be sent to the Mediterranean Sea.

But Mulovsky did not go to the Mediterranean either: the war with Sweden began, and he was appointed commander of the Mstislav frigate, where the young midshipman Ivan Kruzenshtern served under his command, who was destined to lead the first Russian circumnavigation in fifteen years. Mulovsky distinguished himself in the famous Battle of Gogland, for which on April 14, 1789 he was promoted to captain of the brigadier rank. Kireevsky and Trubetskoy received the same rank during the Russian-Swedish war. Three months later, on July 18, 1789, Mulovsky died in a battle near the island of Eland. His death and the outbreak of the French Revolution dramatically changed the situation. The resumption of circumnavigation was forgotten for a decade.

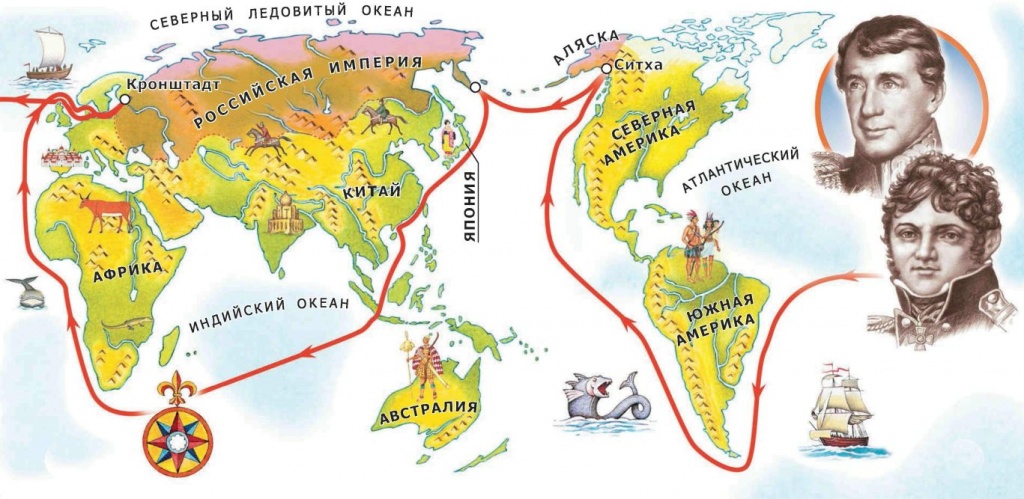

The first Russian circumnavigation of the world under the command of Ivan Fedorovich (Adam-Johann-Friedrich) Krusenstern (1803–1806)

The organization of the first, finally held, Russian circumnavigation is associated with the name of Ivan Fedorovich (Adam-Johann-Friedrich) Krusenstern. In 1788, when "due to a lack of officers" it was decided to prematurely release the midshipmen of the Naval Corps, who at least once went to sea, Kruzenshtern and his friend Yuri Lisyansky ended up serving in the Baltic. Taking advantage of the fact that Kruzenshtern served on the Mstislav frigate under the command of G. I. Mulovsky, they turned to him with a request to allow them to take part in a round-the-world voyage after the end of the war and received consent. After the death of Mulovsky, they began to forget about swimming, but Kruzenshtern and Lisyansky continued to dream about it. As part of a group of Russian naval officers, they were sent to England in 1793 to get acquainted with the experience of foreign fleets and gain practical skills in sailing across the expanses of the ocean. Krusenshern spent about a year in India, sailed to Canton, lived for six months in Macau, where he got acquainted with the state of trade in the Pacific Ocean. He drew attention to the fact that foreigners brought furs to Canton by sea, while Russian furs were delivered by land.

During the absence of Kruzenshtern and Lisyansky in Russia in 1797, the American United Company arose, in 1799 it was renamed the Russian-American Company (RAC). The imperial family was also a shareholder of RAK. Therefore, the company received the monopoly right to exploit the wealth of Russian possessions on the Pacific coast, trade with neighboring countries, build fortifications, maintain military forces, and build a fleet. The government entrusted her with the task of further expanding and strengthening Russian possessions in the Pacific. But the main problem of the RAC was the difficulty in delivering cargo and goods to Kamchatka and Russian America. The overland route through Siberia took up to two years and was costly. Cargoes often arrived spoiled, products were fabulously expensive, and equipment for ships (ropes, anchors, etc.) had to be divided into parts, and spliced and joined on the spot. Valuable furs mined in the Aleutian Islands often ended up in St. Petersburg spoiled and sold at a loss. Trade with China, where there was a great demand for furs, went through Kyakhta, where furs got from Russian America through Petropavlovsk, Okhotsk, Yakutsk. In terms of quality, the furs brought to the Asian markets in this way were inferior to the furs delivered to Canton and Macau by American and British ships in an immeasurably shorter time.

Upon his return to Russia, Kruzenshtern submitted two memorandums to Paul I justifying the need to organize round-the-world voyages. Kruzenshtern also proposed a new procedure for training maritime personnel for merchant ships. To the six hundred cadets of the Naval Corps, he proposed to add another hundred people from other classes, mainly from ship's cabin boys, who would study together with noble cadets, but would be assigned to serve on commercial ships. The project was not accepted.

With the coming to power of Alexander I in 1801, the leadership of the College of Commerce and the Naval Ministry (the former Admiralty College) changed. On January 1, 1802, Kruzenshtern sent a letter to N. S. Mordvinov, vice-president of the Admiralty College. In it, he proposed his plan for circumnavigating the world. Kruzenshtern showed measures to improve the position of Russian trade on the international market, protect Russian possessions in North America, and provide them and the Russian Far East with everything necessary. Much attention in this letter is paid to the need to improve the situation of the inhabitants of Kamchatka. Kruzenshtern's letter was also sent to the Minister of Commerce and the Director of Water Communications and the Commission for the Construction of Roads in Russia, Count Nikolai Petrovich Rumyantsev. The head of the RAC, Nikolai Petrovich Rezanov, also became interested in the project. Rezanov's petition was supported by Mordvinov and Rumyantsev.

In July 1802, it was decided to send two ships around the world. The official goal of the expedition was to deliver the Russian embassy to Japan, headed by N.P. Rezanov. The costs of organizing this voyage were covered jointly by the RAC and the government. On August 7, 1802, I.F. Kruzenshtern was appointed head of the expedition. Its main tasks were defined: delivery of the first Russian embassy to Japan; delivery of provisions and equipment to Petropavlovsk and Novo-Arkhangelsk; geographical surveys along the route; inventory of Sakhalin, the estuary and the mouth of the Amur.

I. F. Kruzenshtern believed that a successful voyage would raise Russia's prestige in the world. But the new head of the Naval Ministry, P. V. Chichagov, did not believe in the success of the expedition and offered to sail on foreign ships with hired foreign sailors. He ensured that the ships of the expedition were bought in England, and not built at Russian shipyards, as suggested by Kruzenshtern and Lisyansky. To purchase ships, Lisyansky was sent to England, he bought two sloops with a displacement of 450 and 370 tons for 17 thousand pounds and spent another 5 thousand on their repair. In June 1803 the ships arrived in Russia.

departure

And then came the historic moment. On July 26, 1803, the sloop “Nadezhda” and “Neva” left Kronstadt under the general leadership of I.F. Krusenshern. They were supposed to go around South America and reach the Hawaiian Islands. Then their paths diverged for a while. The task of "Nadezhda" under the command of Kruzenshtern included the delivery of goods to the Peter and Paul Harbor and then sending the mission of N.P. Rezanov to Japan, as well as the exploration of Sakhalin. The Neva, under the leadership of Yu. F. Lisyansky, was supposed to go with cargo to Russian America. The arrival of a warship here was to demonstrate the determination of the Russian government to protect the acquisitions of many generations of its sailors, merchants and industrialists. Then both ships were to be loaded with furs and set off for Canton, from where they, after passing the Indian Ocean and rounding Africa, were to return to Kronstadt and complete their circumnavigation there. This plan has been fully implemented.

Crews

The commanders of both ships put a lot of effort into turning a long voyage into a school for officers and sailors. Among the officers of Nadezhda there were many experienced sailors who later glorified the Russian fleet: the future admirals Makar Ivanovich Ratmanov and the discoverer of Antarctica Faddey Faddeevich Belingshausen, the future leader of two round-the-world voyages (1815-1818 and 1823-1826) Otto Evstafievich Kotzebue and his brother Moritz Kotzebue, Fyodor Romberg, Pyotr Golovachev, Ermolai Levenshtern, Philip Kamenshchikov, Vasily Spolokhov, artillery officer Alexei Raevsky and others. In addition to them, the crew of the Nadezhda included Dr. Karl Espenberg, his assistant Ivan Sidgam, astronomer I.K. Horner, naturalists Wilhelm Tilesius von Tilenau, Georg Langsdorf. Major Yermolai Fredericy, Count Fyodor Tolstoy, court adviser Fyodor Fos, painter Stepan Kurlyandtsev, physician and botanist Brinkin were present in the retinue of chamberlain N.P. Rezanov.

On the Neva were officers Pavel Arbuzov, Pyotr Povalishin, Fedor Kovedyaev, Vasily Berkh (later a historian of the Russian fleet), Danilo Kalinin, Fedul Maltsev, Dr. Moritz Liebend, his assistant Alexei Mutovkin, RAC clerk Nikolai Korobitsyn and others. In total, 129 people participated in the voyage. Kruzenshtern, who sailed for six years on English ships, notes: “I was advised to accept several foreign sailors, but, knowing the predominant properties of Russian ones, whom I even prefer to English ones, I did not agree to follow this advice.”

Academician Kruzenshtern

Shortly before leaving, on April 25, 1803, Krusenstern was elected a corresponding member of the Academy of Sciences. Prominent scientists of the Academy took part in the development of instructions for various branches of scientific research. The ships were equipped with the best nautical instruments and aids for those times, the latest scientific instruments.

"Hope" in Kamchatka...

Rounding Cape Horn, the ships parted. After conducting research in the Pacific Ocean, the Nadezhda arrived in Petropavlovsk on July 3, 1804, and the Neva arrived on July 1 in Pavlovsk Harbor on Kodiak Island.

The stay in Petropavlovsk was delayed: they were waiting for the head of Kamchatka, Major General P.I. Koshelev, who was in Nizhnekamchatsk. The Petropavlovsk commandant, Major Krupsky, provided the crew with all possible assistance. “The ship was equipped immediately, and everything was taken to the shore, from which we stood no further than fifty fathoms. Everything belonging to the ship's equipment, after such a long voyage, required either correction or change. Supplies and goods loaded in Kronstadt for Kamchatka were also unloaded,” writes Kruzenshtern. Finally, General Koshelev arrived from Nizhnekamchatsk with his adjutant, younger brother Lieutenant Koshelev, Captain Fedorov and sixty soldiers. In Petropavlovsk, there were changes in the composition of the embassy of N.P. Rezanov to Japan. Lieutenant Tolstoy, Dr. Brinkin and the painter Kurlyandtsev went to Petersburg by land. The embassy included the captain of the Kamchatka garrison battalion Fedorov, lieutenant Koshelev and eight soldiers. In Kamchatka, the Japanese Kiselev, the interpreter (translator) of the embassy, and the “wild Frenchman” Joseph Kabrit, whom the Russians found on the island of Nukagiva in the Pacific Ocean, remained in Kamchatka.

…And in Japan

After repairs and replenishment of supplies, on August 27, 1804, Nadezhda set off with the embassy of N.P. Rezanov to Japan, where she stood in the port of Nagasaki for more than six months. April 5, 1805 "Hope" left Nagasaki. On the way to Kamchatka, she described the southern and eastern coasts of Sakhalin. On May 23, 1805, the Nadezhda again arrived in Petropavlovsk, where N.P. Rezanov and his retinue left the ship and on the RAC ship St. Maria" went to Russian America on Kodiak Island. The results of Rezanov's voyage to Japan were reported by the head of Kamchatka, P.I. Koshelev, to the Siberian governor Selifontov.

From June 23 to August 19, Kruzenshtern sailed in the Sea of Okhotsk, off the coast of Sakhalin, in the Sakhalin Bay, where he carried out hydrographic work and, in particular, studied the estuary of the Amur River - he was engaged in solving the "Amur issue". On September 23, 1805, the Nadezhda finally left Kamchatka and, with a cargo of furs, went to Macau, where she was supposed to meet with the Neva and, loaded with tea, return to Kronstadt. They left Macau on January 30, 1806, but the ships parted at the Cape of Good Hope. The Neva arrived in Kronstadt on July 22, and the Nadezhda arrived on August 7, 1806. Thus ended the first round-the-world voyage of Russian sailors.

Geographic discoveries (and misconceptions)

It was marked by significant scientific results. Both ships carried out continuous meteorological and oceanological observations. Kruzenshtern described: the southern shores of the Nukagiva and Kyushu islands, the Van Diemen Strait, the islands of Tsushima, Goto and a number of others adjacent to Japan, the northwestern shores of the islands of Honshu and Hokkaido, as well as the entrance to the Sangar Strait. Sakhalin was put on the map almost along its entire length. But Kruzenshtern failed to complete his research in the Amur estuary, and he made an incorrect conclusion about the peninsular position of Sakhalin, extending the erroneous conclusion of La Perouse and Broughton for forty-four years. Only in 1849, G. I. Nevelskoy established that Sakhalin is an island.

Conclusion

Krusenstern left an excellent description of his voyage, the first part of which was published in 1809, and the second in 1810. Soon it was reprinted in England, France, Italy, Holland, Denmark, Sweden and Germany. The description of the trip was accompanied by an atlas of maps and drawings, among which were the "Map of the North-Western Part of the Great Ocean" and "Map of the Kuril Islands". They were a significant contribution to the study of the geography of the northern part of the Pacific Ocean. Among the drawings made by Tilesius and Horner, there are views of the Peter and Paul harbor, Nagasaki and other places.

At the end of the voyage, Kruzenshtern received many honors and awards. So, in honor of the first Russian circumnavigation, a medal with his image was knocked out. In 1805, Kruzenshtern was awarded the Order of St. Anna and St. Vladimir of the third degree, received the rank of captain of the 2nd rank and a pension of 3,000 rubles a year. Until 1811, Krusenshern was engaged in the preparation and publication of a description of his journey, reports and calculations on the expedition. Officially, he was in 1807-1809. was listed at the Petersburg port. In 1808 he became an honorary member of the Admiralty Department, on March 1, 1809 he was promoted to captain of the 1st rank and appointed commander of the ship "Blagodat" in Kronstadt.

Since 1811, Kruzenshtern began his service in the Naval Cadet Corps as a class inspector. Here he served intermittently until 1841, becoming its director. On February 14, 1819, he was promoted to captain-commander, in 1823 he was appointed a permanent member of the Admiralty Department, and on August 9, 1824, he became a member of the Main Board of Schools. On January 8, 1826, with the rank of Rear Admiral Kruzenshtern, he was appointed assistant director of the Naval Cadet Corps, and from October 14 of the same year he became its director and held this post for fifteen years. He founded a library and a museum, created officer classes for the further education of the most capable midshipmen who graduated with honors from the corps (later these classes were transformed into the Naval Academy). In 1827 he became an indispensable member of the Scientific Committee of the Naval Staff and a member of the Admiralty Council, in 1829 he was promoted to vice admiral, and in 1841 he became a full admiral.

Through the mountains to the sea with a light backpack. Route 30 passes through the famous Fisht - this is one of the most grandiose and significant natural monuments in Russia, the highest mountains closest to Moscow. Tourists travel lightly through all the landscape and climatic zones of the country from the foothills to the subtropics, spending the night in shelters.

Trekking in Crimea - 22 route

From Bakhchisarai to Yalta - there is no such density of tourist facilities as in the Bakhchisarai region anywhere in the world! Mountains and the sea, rare landscapes and cave cities, lakes and waterfalls, secrets of nature and mysteries of history, discoveries and the spirit of adventure are waiting for you... Mountain tourism here is not difficult at all, but any trail surprises.

Adygea, Crimea. Mountains, waterfalls, herbs of alpine meadows, healing mountain air, absolute silence, snowfields in the middle of summer, the murmur of mountain streams and rivers, stunning landscapes, songs around the fires, the spirit of romance and adventure, the wind of freedom are waiting for you! And at the end of the route, the gentle waves of the Black Sea.