Ivan Fyodorovich Kruzenshtern

A number of brilliant geographical studies are known in the history of the first half of the 19th century. Among them, one of the most prominent places belongs to Russian round-the-world travel.

At the beginning of the 19th century, Russia occupied a leading position in the organization and conduct of round-the-world voyages and exploration of the oceans.

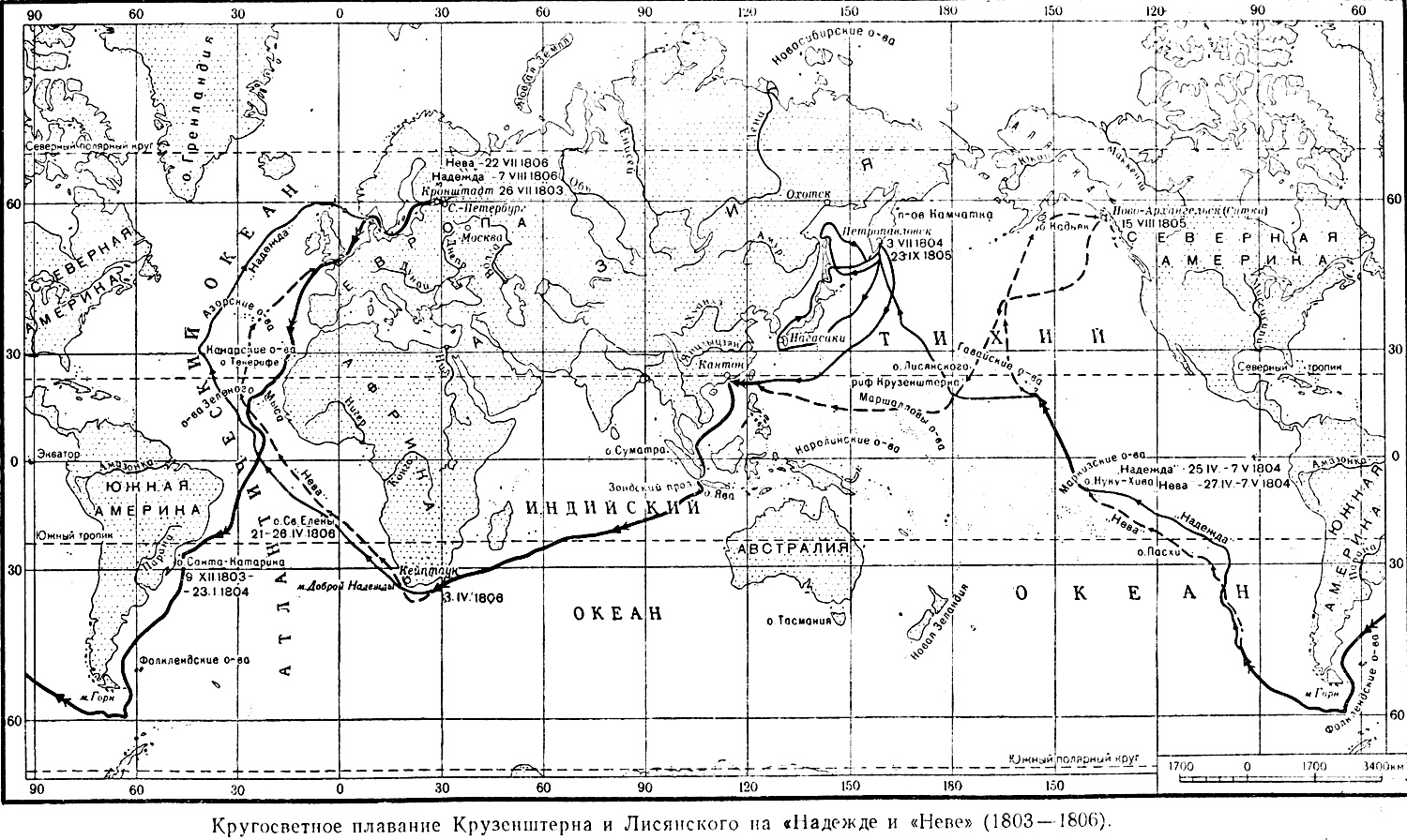

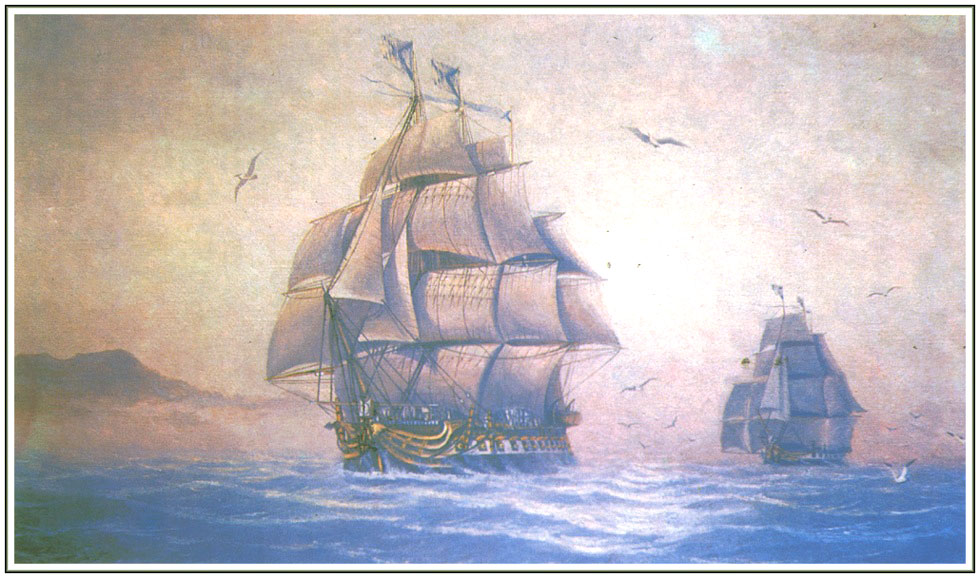

The first voyage of Russian ships around the world under the command of lieutenant commanders I.F. Kruzenshtern and Yu.F. Lisyansky lasted three years, like most of the round-the-world voyages of that time. With this journey in 1803, a whole era of remarkable Russian round-the-world expeditions began.

Yuri Fyodorovich Lisyansky

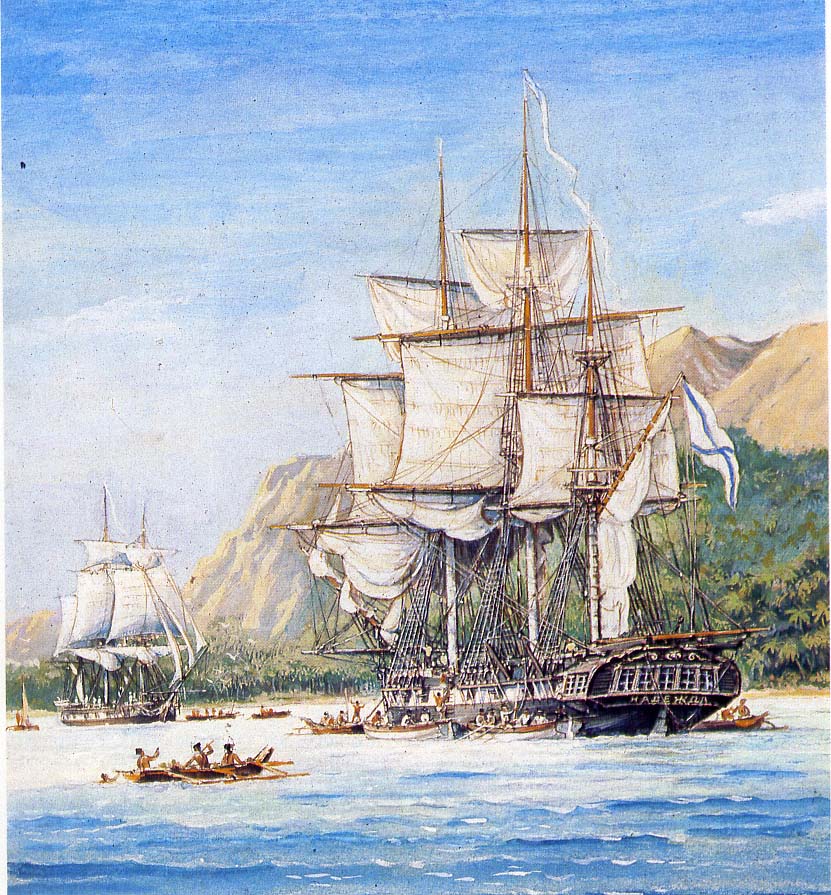

Yu.F. Lisyansky received an order to go to England to buy two ships intended for circumnavigation. These ships, Nadezhda and Neva, Lisyansky bought in London for 22,000 pounds sterling, which was almost the same in gold rubles at the exchange rate of that time. The price for the purchase of "Nadezhda" and "Neva" was actually equal to 17,000 pounds sterling, but for the corrections they had to pay an additional 5,000 pounds. The ship "Nadezhda" has already counted three years from the date of its launch, and the "Neva" is only fifteen months old. "Neva" had a displacement of 350 tons, and "Nadezhda" - 450 tons.

sloop "Hope"

Sloop “Neva”

In England, Lisyansky bought a number of sextants, compasses, barometers, a hygrometer, several thermometers, one artificial magnet, chronometers by Arnold and Pettiwgton, and more. Chronometers were tested by Academician Schubert. All other instruments were Troughton's work. Astronomical and physical instruments were designed to observe longitudes and latitudes and orient the ship. Lisyansky took care to purchase a whole pharmacy of medicines and antiscorbutic drugs, since in those days scurvy was one of the most dangerous diseases during long voyages. Equipment for the expedition was also purchased from England, including comfortable, durable clothing suitable for various climatic conditions for the team. There was a spare set of underwear and dresses. Mattresses, pillows, sheets and blankets were ordered for each of the sailors. The ship's provisions were the best. The crackers prepared in St. Petersburg did not spoil for two whole years, just like saltonia, whose ambassador with domestic salt was produced by the merchant Oblomkov. The Nadezhda team consisted of 58 people, and the Neva of 47. They were selected from volunteer sailors, who turned out to be so many that everyone who wanted to participate in a round-the-world trip could be enough to complete several expeditions. It should be noted that none of the crew members participated in long-distance voyages, since in those days Russian ships did not descend south of the northern tropic. The task that confronted the officers and the expedition team was not easy. They had to cross two oceans, go around the dangerous Cape Horn, famous for its storms, and rise to 60 ° N. sh., to visit a number of little-studied coasts, where sailors could expect uncharted and undescribed pitfalls and other dangers. But the command of the expedition was so confident in the strength of its "officers and ratings" that it rejected the offer to take on board several foreign sailors familiar with the conditions of long-distance voyages. Of the foreigners in the expedition were naturalists Tilesius von Tilenau, Langsdorf and astronomer Horner. Horner was of Swiss origin. He worked at the then famous Seeberg Observatory, the head of which recommended him to Count Rumyantsev. The expedition was also accompanied by a painter from the Academy of Arts. The artist and scientists were together with the Russian envoy to Japan, N.P. Rezanov, and his retinue on board the large ship Nadezhda. "Hope" was commanded by Kruzenshtern. Lisyansky was entrusted with the command of the Neva. Although Kruzenshtern was listed as the commander of the Nadezhda and the head of the expedition for the Naval Ministry, in the instructions transmitted by Alexander I to the Russian ambassador to Japan, N.P. Rezanov, he was called the chief head of the expedition.

N.P. Rezanov

This dual position was the cause of the conflict between Rezanov and Krusenstern. Therefore, Kruzenshtern repeatedly sent reports to the Directorate of the Russian-American Company, where he wrote that he was called upon by the highest order to command the expedition and that "it was entrusted to Rezanov" without his knowledge, to which he would never have agreed that his position "does not consist only in watching the sails", etc.

Great Ancestor Crusius

The Kruzenshtern family gave Russia several generations of travelers and sailors.

Ancestor of the Krusensterns, German diplomat Philip Crusius (1597-1676) in 1633-1635. headed two embassies of the Schleswig-Holstein Duke Frederick III to the Moscow Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich and the Persian Shah Sefi. The travel notes collected by Philip Crusius and the embassy secretary Adam Olearius (1599-1671) formed the basis of the most famous encyclopedic work on Russia in the 17th century. - "Descriptions of a journey to Muscovy and through Muscovy to Persia and back" by Adam Olearius.

Returning from Muscovy, Philip Crusius went to the service of the Swedish Queen Christina and in 1648 received the surname Kruzenshtern and a new coat of arms, crowned with a Persian turban in memory of his journey. In 1659, he became governor of all of Estonia (it then belonged to the Swedes). His grandson, Swedish Lieutenant Colonel Evert Philipp von Krusenstern (1676-1748), a participant in the Northern War, was taken prisoner near Narva in 1704 and lived in exile in Tobolsk for 20 years, and upon his return he bought out the mortgaged patrimonial estates Haggud and Ahagfer. The landowner of the Haggud, Vahast and Perisaar estates was Judge Johann Friedrich von Krusenstern (1724-1791), the admiral's father.

Ivan Fedorovich, the first "Russian" Krusenstern

In Haggud, on November 8, 1770, the most prominent representative of the Kruzenshtern family, Ivan Fedorovich, was born. Biographers usually write that the maritime career for Ivan Fedorovich was chosen by chance and that there were no sailors in the family before him. However, Ivan Fedorovich's father could not help but know about his own cousin Moritz-Adolf (1707-1794), an outstanding admiral of the Swedish fleet.

Ivan Fedorovich Kruzenshtern (1770-1846), having finished the Naval Cadet Corps ahead of schedule due to the outbreak of the Russian-Swedish War (1788-1790), successfully fought the Swedes on the Mstislav ship. In 1793, together with Yu.F. Lisyansky and other young officers were sent "for an internship" to England, where he served on the ships of the English fleet off the coast of North and Central America, sailed to Africa and India. In Philadelphia, both Kruzenshtern and Lisyansky met with American President George Washington. Returning to his homeland, in 1800 Kruzenshtern submitted a project for circumnavigating the world for trade and scientific purposes. The project was initially rejected - the unknown author had no patronage, Russia, which was constantly at war with France at that time, did not have enough funds, and the ministers believed that the country was strong in the land army and it was not appropriate for her to compete at sea with the British.

However, in July 1802, Emperor Alexander I approved the project, leaving Kruzenshtern to carry it out himself. The purchase of the ships "Nadezhda" and "Neva", provisions and all necessary goods was undertaken by the Russian-American company, created to develop Russian possessions in North America - in Alaska, the Aleutian Islands, Kodiak, Sitka and Unalashka. The company's industrialists hunted sea otters, fur seals, arctic foxes, foxes, bears and harvested valuable furs and walrus tusks.

Japanese question

In 1802, the emperor and the minister of commerce had the idea to send an embassy to Japan on the Nadezhda. In Japan, lying close to Kamchatka and Russian America, it was planned to buy rice for Russian settlements in the North. The Japanese embassy was offered to be headed by Chamberlain Nikolai Petrovich Rezanov, one of the organizers and shareholders of the Russian-American Company, its “authorized correspondent”, Chief Prosecutor of the 1st Department of the Senate, Commander of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem. Emperor Alexander clearly did not attach much importance to Rezanov's diplomatic mission. The ambassador, who himself was not a diplomat, received a completely unrepresentative retinue. When sailing from St. Petersburg, the ambassador was not given a soldier - a guard of honor. Later, he managed to "rent" from the Governor-General of Kamchatka P.I. Koshelev two non-commissioned officers, a drummer and five soldiers.

Embassy gifts could hardly interest the Japanese. It was unreasonable to bring porcelain dishes and fabrics to Japan, let's remember the elegant Japanese, Chinese and Korean porcelain and magnificent silk kimonos. Among the gifts intended for the Emperor of Japan were beautiful silver fox furs - in Japan, the fox was considered an unclean animal.

Rezanov was stationed on the main ship "Nadezhda" (under the command of Krusenstern); "Neva" was led by Yu.F. Lisyansky. A whole “scientific faculty” was sailing on the Nadezhda: the Swiss astronomer I.-K. Horner, Germans - doctor, botanist, zoologist and artist V.T. Tilesius; traveler, ethnographer, physician and naturalist G.G. von Langsdorf, MD K.F. Espenberg. There were also talented young people on the ship - 16-year-old cadet Otto Kotzebue, in the future the head of two round-the-world voyages - on the Rurik and on the Enterprise - and midshipman Thaddeus Bellingshausen, the future discoverer of Antarctica.

The hardships of swimming

The Nadezhda was 117 feet (35 m) long and 28 feet 4 inches (8.5 m) wide, the Neva was even smaller. On board the "Nadezhda" were constantly 84 officers, crew and passengers (scientists and N.P. Rezanov's retinue). The ship was also overloaded with goods that were being transported to Okhotsk, provisions for two years; one gift for the Japanese occupied 50 boxes and bales. Because of the tightness and overcrowding, the two highest ranks of the expedition - Kruzenshtern and Rezanov - did not have separate cabins and huddled in one captain's cabin, not exceeding 6 m2 with a minimum ceiling height.

On the ship, on dark tropical nights, they worked by candlelight, they were saved from the cold in high latitudes only by an additional sweatshirt, there were only 3 latrines for 84 people; it was impossible to wash properly because of the constant lack of fresh water. And all this is either in the cold, or in the heat, or in a storm (“Nadezhda” suffered nine severe storms, when the ship almost died), then in the dead calm of the tropics. Exhausting pitching and swell constantly caused seasickness. The "Nadezhda" kept livestock to replenish the diet: pigs, or a pair of bulls, or a cow with a calf, a goat, chickens, ducks, geese. All of them hummed, lowed and grunted in the cages on the deck, they had to be constantly cleaned up, and the pigs were even washed once, thrown overboard and thoroughly rinsed in the Atlantic Ocean.

In October 1803, the expedition entered Tenerife (Canary Islands), on November 14 (26) Russian ships crossed the equator for the first time and celebrated Christmas on the island of Santa Catarina off the coast of Brazil, which amazed sailors with its rich flora and fauna. In Brazil, the Russians spent a whole month while the damaged mast was being changed on the Neva.

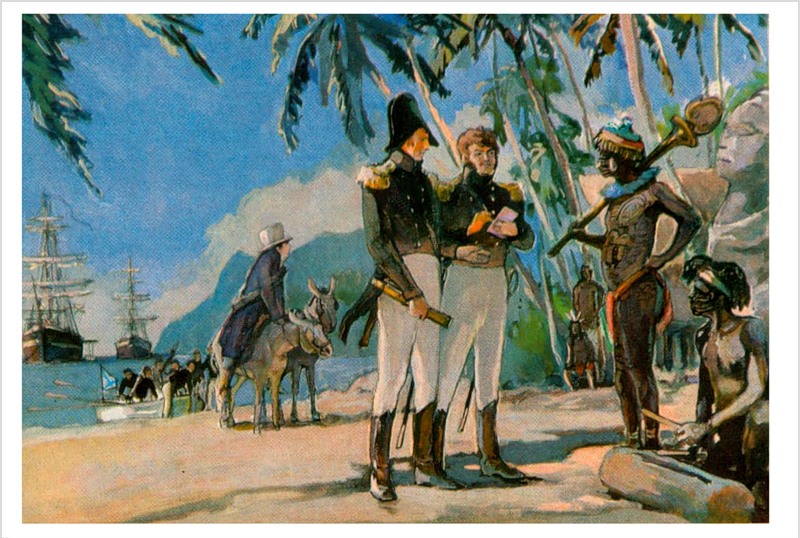

I.F. Kruzenshtern and Yu.F. Lisyansky

After passing Cape Horn, the ships parted during a storm - Lisyansky explored Easter Island, and Kruzenshtern headed straight for Nuku Khiva (Marquesas Islands), where they met in early May 1804. During the transition from Brazil to the Marquesas Islands, drinking water was strictly rationed. Each received a cup of water a day to drink. There was not enough fresh food, the sailors and officers ate corned beef, the food was too monotonous.

In the harsh conditions of navigation, it was necessary not only to survive, but also to work. Officers had to keep watch in any weather, take trigonometric surveys, and sometimes do things themselves that the sailors did not know how or did not want to do. On their shoulders lay the management of loading and unloading, repairing sails and rigging, cranking and searching for leaks. They kept travel journals, studied themselves and taught young people. Naturalists continuously made stuffed fish and birds, preserved and dried sea animals in alcohol, made herbariums, drew and also kept diaries and described scientific observations.

The lieutenants stood on 3 watches: during the day twice for 3 hours and once at night for 4 hours. The sailors had 3 watches for 4 hours and one for 2 hours - from 12 noon to 16.00. Three hours a day were spent on astronomical calculations, an hour on writing a journal.

In Nuku Hiva, Russians, to their surprise, met two Europeans - the Englishman E. Robarts and the Frenchman J. Kabri (who had lived there for 5 years and married local women), who helped load the ships with firewood, fresh water, food and served as translators at communication with local residents. And perhaps they had the most exotic impressions from their acquaintance with Oceania - the Marquesas, Easter and Hawaiian Islands.

Conflict in the Marquesas

The navigation was further complicated by the fact that Rezanov, as the head of the embassy, received, along with Kruzenshtern, the powers of the expedition leader, but announced this only when the ships were approaching Brazil, although he did not show any instructions. The officers simply did not believe him, the appointment of a land man as commander of a circumnavigation was so ridiculous. In the maritime charter, to this day, there is a rule that the captain of the ship in all cases and always is the captain of the ship, at least when crossing by sea.

On the Marquesas Islands, 9 months after sailing from Kronstadt, the confrontation between the officers and Rezanov turned into a quarrel. Kruzenshtern, seeing that pigs could be exchanged with the Marquesans only for iron axes, forbade them to be exchanged for native jewelry and clubs until the ship was supplied with fresh meat: after a difficult transition from Brazil, the crew members were already beginning to have scurvy. Rezanov sent his clerk Shemelin to trade marquis "rarities" for axes. Eventually the price of axes dropped and the Russians were only able to buy a few pigs.

In addition, Nuku Hiva at the beginning of the XIX century. was not a tourist paradise, but an island inhabited by cannibals. The prudent Kruzenshtern did not let the members of his team ashore alone, but only in an organized team under the leadership of officers. Under such conditions, it was necessary to observe the most severe military discipline, possible only with one-man command.

Mutual displeasure turned into a quarrel, and the officers of both ships demanded an explanation from Rezanov and the public announcement of his instructions. Rezanov read the imperial rescript he had and his own instructions. The officers decided that Rezanov compiled them himself, and the emperor approved them without reviewing them in advance. Rezanov, on the other hand, claimed that Kruzenshtern, even before leaving Kronstadt, saw his instructions and knew for sure that it was Rezanov who was the chief commander of the expedition. However, if Kruzenshtern had not been firmly convinced that it was he who was leading the expedition, the project of which he himself proposed, he simply would not have set sail on such terms.

Navy historian N.L. Klado put forward the version that Rezanov presented Kruzenshtern in Kronstadt not with instructions, but only with the highest rescript, in which nothing was said about the order of subordination. To demand from the chamberlain to present instructions regarding his Japanese mission, Lieutenant Commander Kruzenshtern, junior both in rank and in age, clearly could not.

After the conflict in the Marquesas Islands, Rezanov locked himself in his half of the cabin and did not go out on deck, which saved him from the need for explanations.

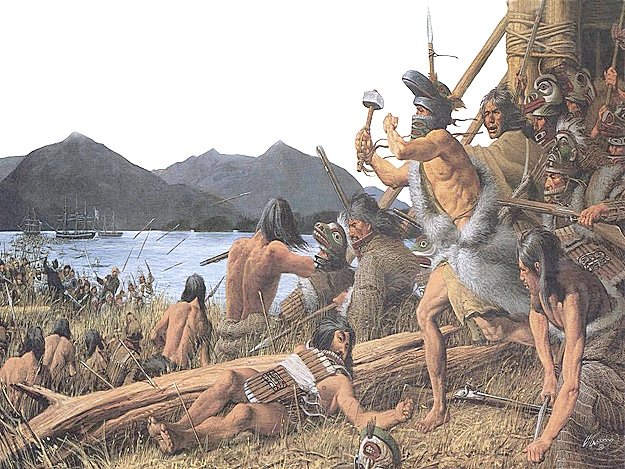

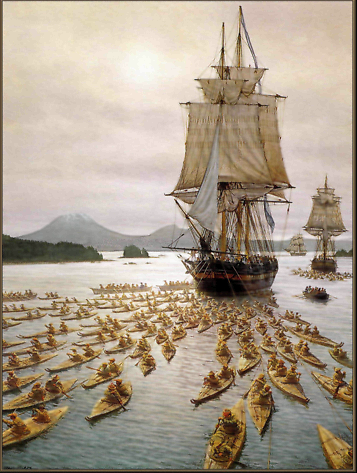

From the Marquesas Islands, both ships reached Hawaii, from where Lisyansky went to Russian America, where he helped the main ruler of the Russian colonies in America, A.A. Baranov to recapture the Sitka fortress captured by the Indians

"Neva" off the coast of Alaska

Landing from the "Neva" (battle with the Indians)

"Hope" arrived in Kamchatka (July 3/15, 1804) and N.P. Rezanov immediately wrote to the Governor-General of Kamchatka P.I. Koshelev, who was then in Nizhne-Kamchatsk. The accusations brought by Rezanov were so severe that the governor-general began an investigation. Realizing the insulting hopelessness of the situation. I.F. Kruzenshtern, with the determination of a man who is confident in his rightness, aggravates the situation to the limit, putting Rezanov before the need to publicly declare his position, and therefore, to bear responsibility for it.

The sustained position of Koshelev contributed to the conclusion of a formal reconciliation, which took place on August 8, 1804.

The further voyage to Japan was already proceeding calmly, there were no discussions about the authorities. The emperor did not move forward with the matter, agreeing that reconciliation in Kamchatka ended the conflict, and in July 1805, after the ship returned from Japan, the Order of St. Anna of the II degree was delivered to Kamchatka from him, and Rezanov - a snuffbox, showered with diamonds, and a gracious rescript dated April 28, 1805, as evidence of his goodwill towards both. Upon returning to St. Petersburg, Kruzenshtern received the Order of St. Vladimir with a rescript putting everything in its place: “To our fleet, Lieutenant Commander Kruzenshtern. Having completed a journey around the world with the desired success, you justified the fair opinion about you, in which, by the will of OUR, you were entrusted with the main leadership of this expedition.

Japan, America, the legend of the "last love"

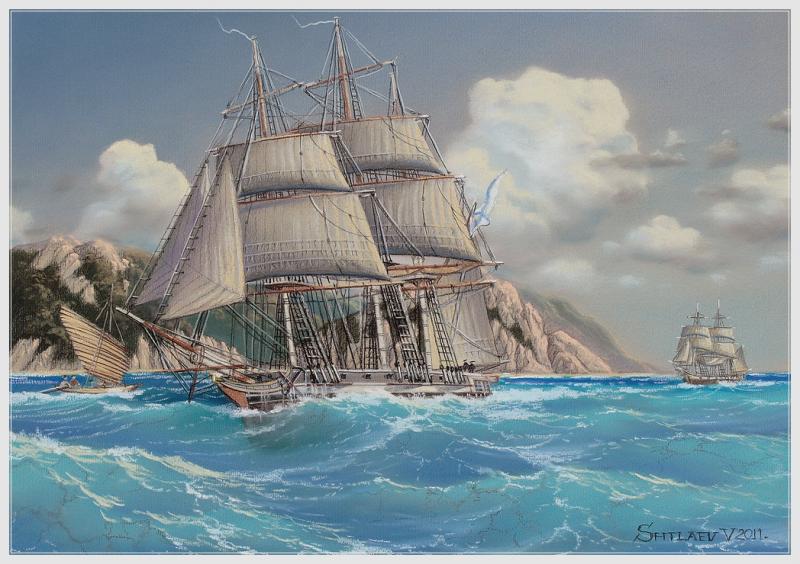

Kruzenshtern, having unloaded company goods in Kamchatka in the summer of 1804, went to Japan, then closed from the whole world, where the Nadezhda, while negotiations were underway with Japanese officials, was anchored near Nagasaki for more than six months (from September 1804 to April 1805

"Hope" off the coast of Japan

The Japanese treated the sailors quite friendly: the ambassador and his retinue were provided with a house and a warehouse for gifts to the Japanese emperor on the shore, the embassy and the crew of the ship were transported daily with fresh products. However, the Japanese government, forcing Rezanov to wait 6 months for an answer, finally refused to accept the embassy and trade with Russia. The reason for the refusal is still not entirely clear: either the orientation of the shogun and his entourage towards isolationist politics played a role, or the unprofessional diplomat Rezanov frightened the Japanese with statements about how great and powerful Russia is (especially compared to small Japan).

In the summer of 1805, Nadezhda returned to Petropavlovsk, and then went to the Sea of Okhotsk to explore Sakhalin. From Kamchatka, chamberlain Rezanov and naturalist Langsdorf went to Russian America on the galliot "Maria", and then on the "Juno" and "Avos" to California, where the chamberlain met his last love - Conchita (Concept Argüello). This story, for centuries, surrounded the name of Rezanov with a romantic halo, inspiring many writers. Returning to St. Petersburg through Siberia, Rezanov caught a cold and died in Krasnoyarsk in 1807.

Home...

"Nadezhda" and "Neva" met at the end of 1805 in Macao (southern China), where, having sold a load of furs, they bought tea, fabrics and other Chinese goods. Nadezhda, having entered St. Helena, Helsingor and Copenhagen, returned to Kronstadt on August 7 (19), 1806. The Neva returned two weeks earlier without entering St. Helena.

For most of the way, Kruzenshtern and Lisyansky walked away from the routes already explored and everywhere they tried not only to determine the position of the ship in the most accurate way, but also to correct the maps they had. Kruzenshtern was the first to draw up detailed maps of Sakhalin, Japan, the southern coast of Nuku Khiva (Marquesas Islands), discovered several straits between the Kuril Islands, and Kamennye Trap Islands.

The merits of Kruzenshtern were highly appreciated by the world scientific community. Only one fact: in 1820, that is, during the life of Kruzenshtern, a book was published in London containing an overview of the main circumnavigations of all times and peoples, called "From Magellan to Kruzenshtern."

The first Russian round-the-world expedition strengthened Russia's positions in the northern part of the Pacific Ocean and drew attention not only to Kamchatka and Sakhalin, but also to the polar regions north of the Bering Strait.

Legacy of the first circumnavigation

Although the participants in the first Russian circumnavigation in the first quarter of the 19th century. published a number of works and descriptions of their journey, many of them have long become a bibliographic rarity, and some have not yet been published and are stored in archives. The most famous published work of Kruzenshtern is "Journey around the world."

But not in any edition of the XIX century. there are no such picturesque details of the circumnavigation as in the diaries of the lieutenants of the Nadezhda E.E. Levenshtern and M.I. Ratmanova, In 2003, the translation of Levenstern's diary was finally published. Ermolai Ermolaevich Levenshtern recorded every day all the funny, funny and even indecent incidents on board the Nadezhda, all the impressions of landing on the shore, especially in exotic countries - in Brazil, Polynesia, Japan, China. The diary of Makar Ivanovich Ratmanov, senior lieutenant of Nadezhda, has not yet been published.

The illustrations are even worse. Along with the out-of-print atlases, there is a whole collection of drawings and sketches that has never been published and seen by few. This gap was partially filled by the album “Around the World with Kruzenshtern”, dedicated to the historical and ethnographic heritage of the participants in the circumnavigation. Comparison of the same objects, places in the drawings of different authors helped to identify geographical objects that were not named in the Kruzenshtern atlas.

Kruzenshtern's voyage introduced not only Russia, but also world science to mysterious Japan. Travelers carried out mapping of the Japanese coast, collected ethnographic materials and drawings. The Russians, while staying in Nagasaki, sketched a huge amount of Japanese utensils, boats, flags and coats of arms (Japanese heraldry is still almost unknown in our country).

The sailors first introduced scientists to two ancient "exotic" peoples - the Ainu (Hokkaido and Sakhalin) and the Nivkhs (Sakhalin). The Russians also called the Ainu "shaggy" smokers: unlike the Japanese, the Ainu had wild shocks of hair on their heads and "shaggy" beards sticking out in different directions. And perhaps the main historical and ethnographic significance of the first Russian circumnavigation of the world is that it captured (in reports and drawings) the life of the Ainu, Nivkhs, Hawaiians, Marquesas before those radical changes that were soon brought about by contacts with Europeans. The engravings of the participants in the voyage of Kruzenshtern are a real treasure for scientists and artists involved in Polynesia, and above all the Marquesas Islands.

Already since the 1830s. Russian engravings began to be replicated, they illustrated books on the islands of Polynesia, art, and most importantly, aboriginal tattoos. It is interesting that the Marquesas still use these engravings: they draw them on tapa (matter from the bark) and sell them to tourists. Particularly popular with marquis artists are Langsdorff's engravings "The Warrior" and "The Young Warrior", although they are very coarse compared to the originals. The "Young Warrior", a symbol of the Marquess' past, is very popular among both locals and tourists. It even became the emblem of the Keikahanui Hotel in Nuku Hiva, one of the many luxury hotels in French Polynesia.

From the expedition of I.F. Kruzenshtern and Yu.F. Lisyansky, the era of Russian ocean voyages began. Following Kruzenshtern and Lisyansky, V.M. rushed to the ocean. Golovnin, O.E. Kotzebue. L.A. Gagemeister, M.N. Vasiliev, G.S. Shishmarev, F.P. Litke, F.P. Wrangel and many others. And just 12 years after the return of Kruzenshtern, Russian sailors F.F. Bellingshausen and M.P. Lazarev led their ships to the South Pole. This is how Russia ended the era of the Great Geographical Discoveries.

I.F. Kruzenshtern was the director of the Naval Cadet Corps, created the Higher Officer Classes, later transformed into the Naval Academy. He abolished corporal punishment in the corps, introduced new disciplines, founded the corps museum with ship models and an observatory. In memory of Kruzenshtern's activities in the Naval Cadet Corps, his office has been preserved, and graduates, maintaining the tradition, put on a vest on the bronze admiral the night before graduation.

monument to I.F. Kruzenshtern in Leningrad

grave of I.F. Kruzenshtern

Modern barque "Kruzenshtern" (training ship for cadets)