Structure and structure. It is almost impossible to give a generalized description of the structure of the tropical rainforest: this most complex plant community exhibits such a variety of types that even the most detailed descriptions are not able to reflect them. A few decades ago, it was believed that a wet forest is always an impenetrable thicket of trees, shrubs, ground grasses, lianas and epiphytes, since it was mainly judged by descriptions of mountain rainforests. Only relatively recently it became known that in some humid tropical forests, due to the dense closure of the crowns of tall trees, sunlight almost does not reach the soil, so the undergrowth is sparse, and one can pass through such forests almost unhindered.

It is customary to emphasize the species diversity of the tropical rainforest. It is often noted that it is unlikely to find two specimens of trees of the same species in it. This is a clear exaggeration, but at the same time, it is not uncommon to find 50-100 species of trees on an area of 1 hectare.

But there are also relatively species-poor, "monotonous" moist forests. These include, for example, special forests, consisting mainly of trees of the dipterocarpaceae family, growing in areas of Indonesia that are very rich in precipitation. Their existence indicates that in these areas the stage of optimal development of tropical rainforests has already been passed. The extreme abundance of precipitation makes it difficult to aerate the soil, as a result, there was a selection of plants that have adapted to living in such places. Similar conditions of existence can also be found in some damp regions of South America and the Congo basin.

The dominant component of the tropical rainforest is trees of different appearance and different heights; they make up about 70% of all species of higher plants found here. There are three tiers of trees - upper, middle and lower, which, however, are rarely clearly expressed. The upper tier is represented by individual giant trees; their height, as a rule, reaches 50-60 m, and the crowns develop above the crowns of trees located below the tiers. The crowns of such trees do not close, in many cases these trees are scattered in the form of individual specimens that seem to be overgrown. On the contrary, the crowns of trees of the middle tier, having a height of 20-30 m, usually form a closed canopy. Due to the mutual influence of neighboring trees, their crowns are not as wide as those of the trees of the upper tier. The degree of development of the lower tree layer depends on the illumination. It is made up of trees reaching an average of about 10 meters in height. A special section of the book will be devoted to lianas and epiphytes found in different tiers of the forest (pp. 100-101).

Often there is also a tier of shrubs and one or two tiers of herbaceous plants, they are representatives of species that can develop under minimal illumination. Since the humidity of the surrounding air is constantly high, the stomata of these plants remain open throughout the day and the plants are not in danger of wilting. Thus, they constantly assimilate.

According to the intensity and nature of growth, the trees of the tropical rainforest can be divided into three groups. The first are species whose representatives grow rapidly, but do not live long; they are the first to develop where light areas are formed in the forest, either naturally or as a result of human activity. These light-loving plants stop growing after about 20 years and give way to other species. Such plants include, for example, the South American balsa tree ( Ochroma lagopus) and numerous myrmecophilous species of cecropia ( Cecropia), an African species Musanga cecropioides and representatives of the Euphorbiaceae family growing in tropical Asia, belonging to the genus Macaranga.

The second group includes species whose representatives also grow rapidly in the early stages of development, but their growth in height lasts longer, and at the end of it they are able to live for a very long time, probably more than one century. These are the most characteristic trees of the upper tier, the crowns of which are usually not shaded. These include many economically important trees, the wood of which is commonly called "mahogany", for example, species belonging to the genera Swietenia(tropical America), Khaya And Entandrophragma(tropical Africa).

Finally, the third group includes representatives of shade-tolerant species that grow slowly and are long-lived. Their wood is usually very heavy and hard, it is difficult to process it, and therefore it does not find such a wide application as the wood of trees of the second group. Nevertheless, the third group includes species that give noble wood, in particular Tieghemella heckelii or Aucomea klainiana, the wood of which is used as a substitute for mahogany.

Most of the trees are characterized by straight, columnar trunks, which often, without branching, rise to more than 30 meters in height. Only there, a spreading crown develops in isolated giant trees, while in the lower tiers, as already mentioned, the trees, due to their close arrangement, form only narrow crowns.

In some species of trees near the bases of the trunks, board-shaped roots form (see figure), sometimes reaching a height of up to 8 m. They give the trees greater stability, since the root systems that develop shallowly do not provide a strong enough fixation for these huge plants. The formation of plank roots is genetically determined. Representatives of some families, such as Moraceae (mulberry), Mimosaceae (mimosa), Sterculiaceae, Bombacaceae, Meliaceae, Bignoniaceae, Combretaceae, have them quite often, while others, such as Sapindaceae, Apocynaceae, Sapotaceae, do not have them at all.

Trees with plank roots most often grow in damp soils. It is possible that the development of plank-like roots is associated with poor aeration characteristic of such soils, which prevents the secondary growth of wood on the inner sides of the lateral roots (it is formed only on their outer sides). In any case, trees growing on permeable and well-aerated soils of mountain rainforests do not have plank roots.

Trees of other species are characterized by stilted roots; they are formed above the base of the trunk as adnexal and are especially common in trees of the lower tier, also growing mainly in damp habitats.

Differences in the microclimate characteristic of different tiers of the tropical rainforest are also reflected in the structure of the leaves. While upper-story trees usually have elliptical or lanceolate outlines, smooth and dense leathery leaves like laurel leaves (see figure on page 112), able to tolerate alternating dry and wet periods during the day, the leaves of lower-story trees exhibit signs indicating intensive transpiration and rapid removal of moisture from their surface. They are usually larger; their plates have special points on which water collects and then drops from them, so there is no water film on the leaf surface that would prevent transpiration.

The change of foliage in trees of humid tropical forests is not affected by external factors, in particular drought or cold, although here, too, a certain periodicity, which varies in different species, can be replaced. In addition, some independence of individual shoots or branches is manifested, so not the whole tree is leafless at once, but only part of it.

Features of the climate of the humid tropical forest also affect the development of foliage. Since there is no need to protect the points of growth from cold or drought, as in temperate regions, the buds are relatively weakly expressed and are not surrounded by bud scales. With the development of new shoots, many trees of the tropical rainforest experience "drooping" of the leaves, which is caused exclusively by the rapid increase in their surface. Due to the fact that mechanical tissues do not form as quickly, young petioles at first, as if withered, hang down, the foliage seems to droop. The formation of the green pigment - chlorophyll - can also be slowed down, and young leaves turn whitish or - due to the content of the anthocyanin pigment - reddish (see figure above).

"drooping" of the young leaves of the chocolate tree (Theobroma cacao)

The next feature of some tropical rain forest trees is caulifloria, that is, the formation of flowers on the trunks and leafless parts of the branches. Since this phenomenon is observed primarily in the trees of the lower tier of the forest, scientists interpret it as an adaptation to pollination with the help of bats (chiropterophilia), which is often found in these habitats: pollinating animals - bats and bats - when approaching a tree, it is more convenient to grab flowers .

Birds also play a significant role in the transfer of pollen from flower to flower (this phenomenon is called "ornithophilia"). Ornithophilous plants are conspicuous by the bright colors of their flowers (red, orange, yellow), while chiropterophilous plants usually have inconspicuous, greenish or brownish flowers.

A clear distinction between the tiers of shrubs and grasses, as, for example, is typical for the forests of our latitudes, practically does not exist in tropical rainforests. One can only note the upper tier, which, along with tall large-leaved representatives of the banana, arrowroot, ginger and aroid families, includes shrubs and young undergrowth of trees, as well as the lower tier, represented by undersized, extremely shade-tolerant herbs. In terms of the number of species, herbaceous plants in the tropical rainforest are inferior to trees; but there are also such lowland moist forests that have not experienced human influence, in which only one tier of grasses poor in species is generally developed.

Attention is drawn to the fact of variegation, which has not yet found an explanation, as well as the presence of metallic-shiny or matte-velvety surface areas on the leaves of plants living in the subsoil layer of grasses of a humid tropical forest. Obviously, these phenomena are to some extent related to the optimal use of the minimum amount of sunlight that reaches such habitats. Many "variegated" plants of the lower tier of rainforest grasses have become favorite indoor ornamental plants, such as species of the genera Zebrina, Tradescantia, Setcreasea, Maranta, Calathea, Coleus, Fittonia, Sanchezia, Begonia, Pilea and others (figure on page 101). The deep shade is dominated by various ferns, mosquitoes ( Selaginella) and mosses; the number of their species is especially great here. So, most species of mosquitoes (and there are about 700 of them) are found in tropical rainforests.

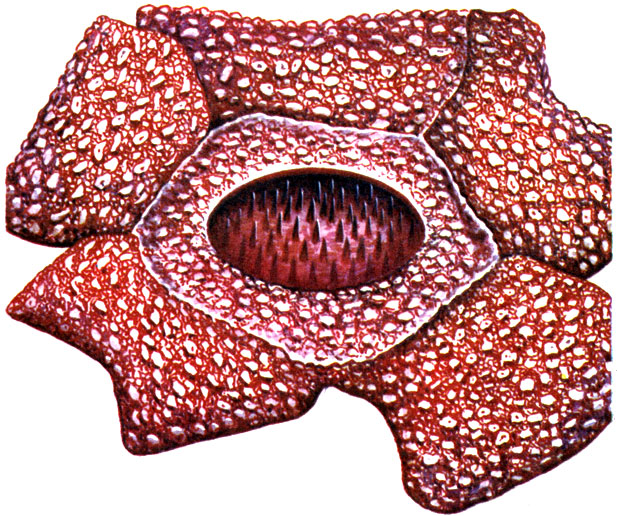

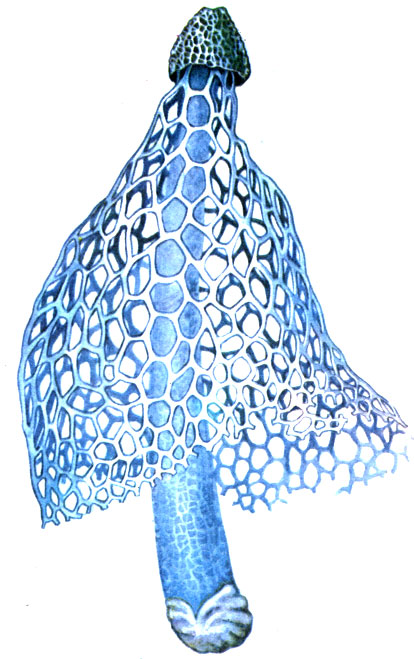

Also noteworthy are saprophytic (that is, using decaying organic matter) fungi of the Clathraceae and Phallaceae families living on the soil of tropical rainforests. They have peculiar fruiting bodies - "mushroom-flowers" (see the picture on page 102).

Lianas. If you swim through the tropical rain forest along the river, the abundance of lianas (plants with woody stems climbing trees) is striking - they, like a dense curtain, cover the trees growing along the banks. Lianas are one of the most amazing components of the vegetation cover of tropical regions: over 90% of all their species are found only in the tropics. Most grow in moist forests, although they require good lighting to thrive. That is why they do not occur everywhere with the same frequency. First of all, they can be seen along the forest edges, in naturally formed lightened areas of the forest and - at least sometimes - in the layers of woody plants that are permeable to the sun's rays (see the figure on page 106). They are especially abundant on plantations established in areas of tropical rainforests, and in secondary forests that appear in clearings. In the lowland moist forests, which have not experienced the influence of man, where the dense, well-developed crowns of trees are tightly closed, creepers are relatively rare.

According to the method of fixing on the plants that serve as their support, creepers can be divided into different groups. For example, leaning creepers can be held on other plants with the help of supporting (clinging) shoots or leaves, thorns, thorns, or special outgrowths such as hooks. Typical examples of such plants are rattan palms of the genus Calamus, 340 species of which are distributed in the tropics of Asia and America (see the figure on page 103).

Rooted creepers are held on a support with the help of many small adventitious roots or cover it with longer and thicker roots. These are many shade-tolerant vines from the aroid family, for example, species of the genera Philodendron, Monstera, Raphidophora, Syngonium, Pothos, Scindapsus, as well as vanilla ( vanilla) is a genus from the orchid family.

Curly vines cover the support with internodes that grow strongly in length. Usually, as a result of subsequent thickening and lignification, such shoots are fixed tightly. Most tropical vines belong to the climbing group, for example, representatives of the mimosa family and the related Caesalpinia family, rich in species and common throughout the tropics, in particular climbing entada ( Entada scandens); the beans of the latter reach 2 m in length (see drawing on page 104). To the same group belong the so-called monkey ladder, or sarsaparilla bauginia ( Bauhinia smilacina), forming thick woody shoots, as well as creepers with bizarre flowers (species of kirkazon, Aristolochia; kirkazon family) (see figure on page 103).

Finally, the vines attached with tendrils form lignified tendrils - with which they cling to the plants that serve as their support. These include representatives of the genus distributed throughout the tropics. Cissus from the Vinogradov family, different types of legumes, in particular (see figure), as well as types of passionflower ( Passiflora; family of passionflowers).

Epiphytes. Extremely interesting are the adaptations to the conditions of existence in tropical rainforests in the so-called epiphytes - plants that live on trees. The number of their species is very large. They abundantly cover the trunks and branches of trees, due to which they are quite well lit. Developing high on trees, they lose the ability to get moisture from the soil, so the supply of water becomes a vital factor for them. It is not surprising that there are especially many types of epiphytes where precipitation is plentiful and the air is humid, but for their optimal development, it is not the absolute amount of precipitation that is decisive, but the number of rainy and foggy days. The unequal microclimate of the upper and lower tree layers is also the reason why the communities of epiphytic plants living there are very different in species composition. In the outer parts of the crowns, light-loving epiphytes dominate, while shade-tolerant ones dominate inside, in constantly wet habitats. Light-loving epiphytes are well adapted to the change of dry and wet periods of time that occurs during the day. As the examples below show, they use different possibilities to do this (picture on page 105).

In orchids, represented by a huge number of species (and most of the 20,000-25,000 orchid species are epiphytes), thickened areas of shoots (the so-called bulbs), leaf blades or roots serve as organs that store water and nutrients. This lifestyle is also facilitated by the formation of aerial roots, which are covered on the outside with layers of cells that quickly absorb water (velamen).

Tropical rainforest plants growing in the ground layer

The family of bromeliads, or pineapples (Bromeliaceae), whose representatives are distributed, with one exception, in North and South America, consists almost only of epiphytes, whose rosettes of leaves, similar to funnels, serve as catchment reservoirs; of these, water and nutrients dissolved in it can be absorbed by scales located at the base of the leaves. Roots serve only as organs that attach plants.

Even cacti (for example, species of genera Epiphyllum, Rhipsalis, Hylocereus And Deamia) grow as epiphytes in mountain rainforests. With the exception of a few species of the genus Rhipsalis, also found in Africa, Madagascar and Sri Lanka, they all grow only in America.

Some ferns, such as the bird's nest fern, or nesting asplenium ( Aspleniumnidus), and deer-antler fern, or deer-horned platicerium ( Platycerium), due to the fact that the first leaves form a funnel-shaped rosette, and the second has special leaves adjacent to the trunk of the supporting tree, like patch pockets (picture on page 105), they are even able to create a soil-like, constantly moist substrate in which their roots grow.

Epiphytes that develop in shaded habitats are primarily represented by the so-called hygromorphic ferns and mosses, which have adapted to existence in a humid atmosphere. The most characteristic components of such communities of epiphytic plants, which are especially pronounced in mountain moist forests, are hymenophyllous, or thin-leaved, ferns (Hymenophyllaceae), for example, representatives of the genera Hymenophyllum And Trichomanes. As for lichens, they do not play such a big role because of their slow growth. Of the flowering plants in these communities, there are species of the genera Peperomia And Begonia.

Even the leaves, and above all the leaves of the trees of the lower tiers of the humid tropical forest, where the humidity of the air is constantly high, can be inhabited by various lower plants. This phenomenon is called epiphylly. Lichens, hepatic mosses and algae mostly settle on the leaves, forming characteristic communities.

A kind of intermediate step between epiphytes and vines are hemiepiphytes. They either grow first as epiphytes on tree branches, and as aerial roots form, reaching the soil, they become plants that strengthen themselves in the soil, or in the early stages they develop as lianas, but then lose contact with the soil and thus turn into epiphytes. The first group includes the so-called strangler trees; their aerial roots, like a net, cover the trunk of the support tree and, growing, prevent its thickening to such an extent that the tree eventually dies off. And the totality of aerial roots then becomes, as it were, a system of "trunks" of an independent tree, in the early stages of development of the former epiphyte. The most characteristic examples of strangler trees in Asia are species of the genus Ficus(mulberry family), and in America - representatives of the genus Clusia(St. John's wort family). The second group includes species of the aroid family.

Lowland evergreen tropical rainforests. Although the floristic composition of tropical rain forests in different parts of the globe is very different, and the three main areas of such forests show only a slight similarity in this respect, nevertheless, similar modifications of the main type can be found everywhere in the nature of their vegetation.

The prototype of the tropical rainforest is considered to be an evergreen tropical rainforest of unflooded lowlands that are not damp for a long time. This is, so to speak, a normal type of forest, the structure and features of which we have already spoken about. Forest communities of river floodplains and flooded lowlands, as well as swamps, differ from it in usually less rich species composition and the presence of plants that have adapted to existence in such habitats.

Floodplain rainforests found in close proximity to rivers in regularly flooded areas. They develop in habitats formed as a result of the annual deposition of nutrient-rich river sediment - tiny particles brought by the river suspended in water and then settled. The so-called "white-water" rivers bring this muddy water mainly from the treeless regions of their basins *. The optimal content of nutrients in the soil and the relative supply of running water with oxygen determine the high productivity of plant communities developing in such habitats. Floodplain rainforests are difficult to access for human development, so they have largely retained their originality to this day.

* (Rivers, called "white water" by the authors of this book, in Brazil are usually called white (rios blancos), and "black water" - black (rios negros). White rivers carry muddy water rich in suspended particles, but the color of the water in them can be not only white, but also gray, yellow, etc. In general, the rivers of the Amazon basin are characterized by an amazing variety of water colors. Black rivers are usually deep; the waters in them are transparent - they seem dark only because there are no suspended particles in them that reflect light. Humic substances dissolved in water only enhance this effect and, apparently, affect the color shade.)

Tropical rainforest vines

Moving from the very bank of the river across the floodplain to its edge, one can identify a characteristic succession of plant communities due to the gradual lowering of the soil surface level from high riverbeds to the edge of the floodplain. Riverside forests rich in lianas grow on seldom flooded riverbanks, further from the river turning into a real flooded forest. At the farthest edge of the floodplain, there are lakes surrounded by reed or grass marshes.

Swampy rain forest. In habitats whose soils are almost constantly covered with stagnant or slowly flowing water, marshy tropical rainforests grow. They can be found mainly near the so-called "black-water" rivers, the sources of which are located in forested areas. Therefore, their waters do not carry suspended particles and have a color from olive to black-brown due to the content of humic substances in them. The most famous "black-water" river is the Rio Negro, one of the most important tributaries of the Amazon; it collects water from a vast area with podzolic soils.

In contrast to the floodplain rainforest, swampy forest usually covers the entire river valley. Here there is no deposition of pumps, but, on the contrary, only uniform washing out, therefore the surface of the valley of such a river is even.

Due to the insecurity of habitats, marshy rain forests are not as lush as floodplain forests, and due to the lack of air in the soil, plants with aerial and stilted roots are often found here. For the same reason, the decomposition of organic matter occurs slowly, which contributes to the formation of thick peat-like layers, most often consisting of more or less decomposed wood.

Semi-evergreen lowland moist forests. Some areas of tropical rain forests experience short dry spells that cause leaf changes in the upper forest layer trees. At the same time, the lower tree tiers remain evergreen. Such a transitional stage to dry forests leafed during the rainy season (see p. 120) has been called "semi-evergreen or semi-deciduous lowland moist forests". During dry periods, there can be movement of moisture in the soil from the bottom up, so these forests receive enough nutrients and are very productive.

Epiphytes of the tropical rainforest

Above Asplenium nest Asplenium nidus and below Cattleya citrina

Montane tropical rainforests. The forests described above, whose existence is determined by the presence of water, can be contrasted with those variants of the tropical rainforest, the formation of which is associated with a decrease in temperature; they are mainly found in humid habitats located in different altitudinal zones of the mountainous regions of tropical regions. In the foothill zone, at an altitude of about 400-1000 m above sea level, the tropical rainforest almost does not differ from the lowland forest. It has only two tiers of trees, and the top tier trees are not as tall.

On the other hand, the tropical rain forest of the mountain belt, or, as they say, the mountain rain forest, growing at an altitude of 1000-2500 m, reveals more significant differences. It also has two tree layers, but they are often difficult to identify, and their upper limit often does not exceed 20 m. In addition, there are fewer types of trees here than in the moist forests of the lowlands, and some characteristic features of the trees of such forests, in particular, are absent. roots, as well as caulifloria. Tree leaves are usually smaller and do not have points to remove water droplets.

The shrub and grass layers are often dominated by ferns and bamboo species. Epiphytes are very abundant, while large creepers are rare.

At even higher altitudes in the permanently humid tropics (2500-4000 m), mountain rainforests give way to subalpine mountain forests that develop at cloud level (see t. 2).